My Grad-School Experience: Observation and Experiment

- Audrey White

- May 2, 2024

- 3 min read

Updated: May 22, 2024

Our time in the UK has officially ended. Coming home has me feeling all the emotions (one of which is excitement to finally sleep on our own mattress again). The theme of our life for the past two years has been transience. Corbin narrowed his wardrobe down to four shirts and three pairs of pants. I abandoned over thirty pounds of art supplies from my luggage. We got used to saying goodbye to friends.

Cambridge is full of people pursuing their passion, no matter how economically non-viable it may be. It’s the only place I’ve lived where the first question you’re asked is “What are you working on?” Oh, how I’ll miss it.

I’ve been reflecting on my time in grad school and thought it’d be interesting to put my thoughts into writing. Two years ago, I would have loved to read a blog post all about getting an MA at the Cambridge School of Art. This particular post will just cover the first module:

Before Cambridge, I resided squarely inside the Utah art bubble; a bubble favoring academic drawing, realism, and commercial illustration. Over the course of my undergrad, I had slowly fallen into more convenient methods of art-making, reaching for my paints less and less, and my iPad more and more. Soon enough my style had became synonymous with flat, digital drawings. I’d almost forgotten what my work looked like in traditional mediums.

My digital work fit nicely within the Utah art bubble, but despite many compliments to my work, I felt a separation between myself and the art-making process. With the mechanical predictability of digital tools, I’d lost the joy I experienced from working with my hands, getting messy, and making mistakes.

The UK art bubble couldn’t have been more different. In Cambridge, professors would commend your “sense of place,” or “character of marks.” No one cared about your photorealistic portrait, or perfectly architected perspective. This was a hard transition for me, and I felt it forcefully during the first semester.

• • •

“Observation and Experiment” was by far the hardest module. During the mid-module review, a tutor told me she was concerned about my work, and I needed to double my pace. This shook me. I was working at what felt like break-neck speed for seven hours a day, yet it wasn’t enough.

This spurred dozens of panicky, thoughtless drawings, and a kind of existential art crisis. I didn’t know what art was anymore, let alone how I personally made it. I filled sketchbook after sketchbook with scribbly, careless drawings of whatever I saw. Nothing mattered except filling pages. The ironic thing is these drawings actually received a pretty good response from my tutors (which made me feel even more gaslit).

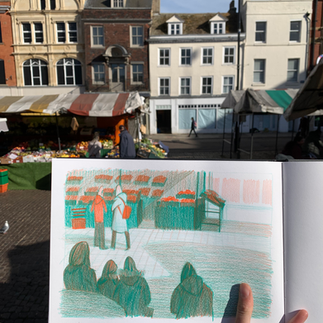

After I burned out from scribbling, I returned to more familiar methods, introducing more constraints: black ink, a thirty minute time-limit, and a couple colored pencils. These rules worked miracles, and I slowly started finding my footing. I fell in love with the wobbly unpredictable nature of ink, and started to have fun again.

"Observation and Experiment" ended after 12 short weeks (followed shortly by “The Sequential Image”). Being a full-time student is a bit like standing in front of an exploding fire hydrant, trying to fill a cup. My panic didn’t end, but I learned better how to manage the chaos.

• • •

Another artist recently told me: “After finishing a course, you need time to unlearn all the material.”

Part of the reason I struggled in “Observation and Experiment” was because I jumped from my undergrad straight into an MA program. In two weeks, I swung from one side of the artistic pendulum to the other.

“Observation and Experiment” was a jarring un-learning of the Utah art bubble. Not only did I have to adapt my work to the pacing and standards of the MA, I had to do it with mediums I hadn’t used in years. Though it was uncomfortable and chaotic, “Observation and Experiment” ultimately strengthened me as an artist. Because of my MA, I’m more playful and imaginative– and I enjoy art more than ever.

This pattern of learning and un-learning is how art plays out over generations. The Romantic painters were un-learned by the Realist painters, and the Realist painters were un-learned by the Impressionist painters. Art history is a conversation between old and new, learning, and unlearning.

In my own practice, it’s important that I regularly swing the pendulum from one side to the other. Doing this prevents me from stagnation, burn out, and thrashing at the bottom of my potential. Going to The Cambridge School of Art was my biggest pendulum swing yet. It shattered everything I thought I knew about what made “good art.”

And now that I’m home, it’s time to unlearn everything.

Comments